Stay updated on news, articles and information for the rail industry

November 2014

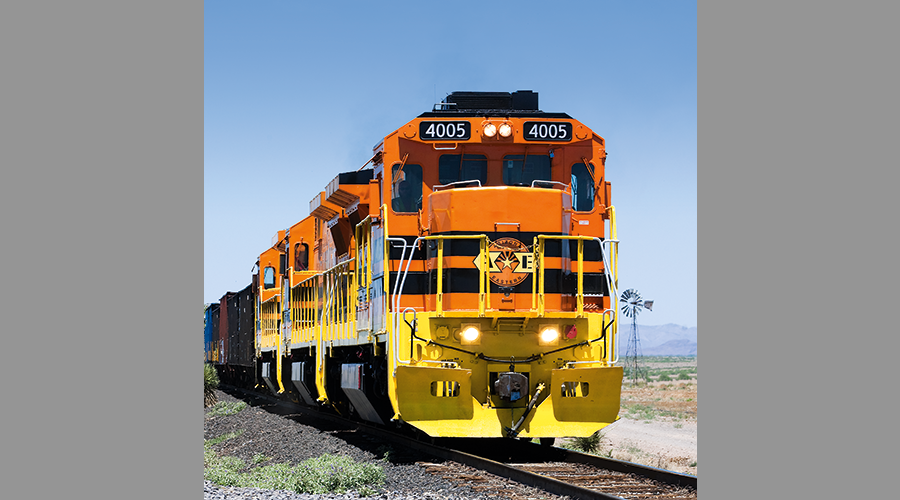

Rail News: Short Lines & Regionals

Indiana Rail Road backs single-person train crews as safe, efficient operating option

— by Jeff Stagl, Managing Editor

During each shift, Frank Rodriguez typically operates an Indiana Rail Road Co. (INRD) train by himself from Indianapolis to Switz City, Ind., and back. The locomotive engineer has covered the 180-mile round trip as a one-person crew for more than 10 years.

Although there isn't anyone to talk to during the trips, Rodriguez prefers to operate a train alone instead of being paired with a crew member who might be difficult to work with.

"I do things the way I want to get them done, and there are no arguments," he says. "I feel more comfortable with it. It's less stressful."

INRD executives believe single-person crews are better than the two-person variety due to operational benefits that can be gleaned at the 500-mile regional, which serves central and southwest Indiana and central Illinois, including such hubs as Chicago, Indianapolis and Louisville, Ky. A one-person crew is ideal for trains that don't need any intermediate switching or require the engineer to leave the cab for any reason, such as trains that complete short runs from point A to point B, the execs say.

INRD has been using the crews that way since 1997, and now employs a single worker on one-third of its 30-plus crew starts each day. The sole train operators don't pose a higher accident risk, according to safety data compiled by the regional, and enable INRD to better manage crew availability and develop tighter work schedules, execs say.

"It gives us a lot of efficiencies and flexibility," says Tom Hoback, INRD's founder, president and chief executive officer.

In the early 1990s, INRD executives began to analyze one-person crews along with locomotive remote-control systems as potential ways to increase operational efficiencies. The execs observed single-person operations at CN and the Wisconsin Central Railroad.

In 1996, they visited a New Zealand railroad that had been employing the crews for 12 years. The execs rode more than 20 single-person- operated trains in one week, says Hoback.

"There was no management on board, so the workers could say what they wanted, and they all said they wouldn't go back to two-person crews," he says. "They said they were all in control of their trains, and they liked the independence. Sometimes, the chemistry was bad with the other guy in the cab."

Before INRD could adopt the crews, a radio communication system was needed to cover the entire railroad and ensure train contact at all times. So, the railroad worked with Wabtec Corp. to develop a radio system, including GPS devices for road locomotives. The system was affordable because it incorporated mostly off-the-shelf products, says Hoback.

Now, a dispatcher calls a train every several miles to maintain communication with the sole worker, and can stop a train if necessary, he says.

INRD execs had talked to Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) officials prior to implementation to explain how the regional would implement one-person crews and discuss the overall plan, says Tom Quigley, who served as INRD's vice president of operations until 2001, and now provides consulting services to CSX Transportation and Union Pacific Railroad.

"There was no regulation in place that said we couldn't do it. We weren't unionized at the time," says Quigley. "We also had our safety team look at it."

When INRD negotiated its first agreement with the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen (BLET) in the late 1990s, the one-person crews were brought up by union officials, but they quickly moved onto other issues, he says. The crews also weren't a major sticking point when the most recent contract was negotiated in 2012, says Quigley.

Rail labor unions question safety

However, one-person crews are a top issue for leaders of both the BLET and Transportation Division of the International Association of Sheet Metal, Air, Rail and Transportation Workers (SMART).

The unions have serious safety concerns about the crews, including the possibility of an accident or incident that could have been prevented had two people operated the train.

Two-person crews are safer because there are checks and balances in train operations involving two people, including a second set of eyes and ears to detect any problems, says SMART Transportation Division President John Previsich, a former Southern Pacific Transportation train-service worker who serves on the FRA's Rail Safety Advisory Committee.

"The job is more complex than just controlling the movement of a train," he says, adding that a train could be hauling hazardous materials, stretch a mile-and-a-half long or need to travel 300 miles to reach its destination, which adds complexity.

Previsich also is concerned that a train controlled by one person could potentially malfunction in a town and tie up grade crossings for a long time until problems are rectified — perhaps longer than if a two-person crew manned the train. The blocked crossing might impede an ambulance or fire truck that's responding to an emergency situation, he says.

Safe Freight Act legislation still pending

The BLET and SMART Transportation Division support the Safe Freight Act (H.R. 3040), a bill introduced in August 2013 that would require two-person crews, including an engineer and conductor certified under FRA regulations.

The Association of American Railroads (AAR) and American Short Line and Regional Railroad Association oppose the legislation because they believe it doesn't adequately consider current industry practices and the overall rail safety record in the United States.

A recent effort by a Class I to employ one-person crews was halted by a vote among SMART Transportation Division members in July.

By a five-to-one margin, the union members rejected a tentative agreement with BNSF Railway Co. that would have enabled trains equipped with positive train control (PTC) to be operated solely by one engineer between certain territories in the Midwest and Pacific Northwest.

The one-person-crew pact would have covered about 60 percent of BNSF's system, but would not have applied to trains carrying large volumes of hazardous materials, including crude oil and ethanol.

An agreement provision that wasn't talked about much stipulated that BNSF could have used the one-person crews only if permitted by the FRA, says Previsich.

But FRA officials believe that for most railroad operations, the use of a multiple-person crew enhances safety. In April, the administration announced plans to issue a proposed rule that would require two-person crews on crude oil trains and establish minimum crew-size standards for most mainline freight- and passenger-rail operations.

If a railroad proposed using single-person operations on a dedicated, separated right of way featuring no grade crossings and controlled by a much higher-functioning PTC system than is available today, "then maybe we can talk about one-man crews," says Previsich.

Indiana Rail Road cites safety data

However, INRD's safety data shows one-person crews are four times safer than conventional crews, says INRD's Hoback.

The AAR continues to analyze the regional's data and so far hasn't reached any conclusions, according to the association.

The railroad has "done its homework" to ensure one-person crews can operate safely on INRD's lines, says Hoback. Not one accident has occurred that could have been prevented if two people were onboard a train, he adds.

"We wouldn't put our workers in harm's way," says Hoback.

Single-person crews know what their responsibilities are, especially since "there's no other guy to carry them," he says. The workers are encouraged to ask questions to help identify issues and ensure safety.

Each engineer is required to take a physical exam prior to becoming a sole train operator. The engineers receive 10 percent of their wages as incentive pay.

Although there was some job-loss apprehension at first, the crews haven't led to any layoffs at INRD, says Hoback.

"We haven't had any layoffs in the history of the railroad, even in the recession," he says.

So far, INRD has derived the operational efficiency and flexibility benefits it had hoped for from the crews, says Hoback.

But if the FRA passes a restrictive rule requiring two-person crews, "it would kill our efficiency" and force the railroad to hire dozens more workers, says INRD General Manager-Transportation Peter Jespersen.

The rule might not gain steam if other railroads supported and adopted more one-person crews.

Although nearly all major railroads have sent representatives to INRD to observe the single-person operations, "we use them more than anyone else, we've been told," says Hoback.

Given the rejection of the BNSF/SMART Transportation Division agreement, no other adoptions appear to be imminent.

"I'm surprised the industry is so timid on this," says Hoback. "It concerns me."

2025 MOW Spending Report: Passenger-rail programs

2025 MOW Spending Report: Passenger-rail programs

Gardner steps down as Amtrak CEO

Gardner steps down as Amtrak CEO

Guest comment: Oliver Wyman’s David Hunt

Guest comment: Oliver Wyman’s David Hunt

Women of Influence in Rail eBook

Women of Influence in Rail eBook

railPrime

railPrime