Stay updated on news, articles and information for the rail industry

November 2011

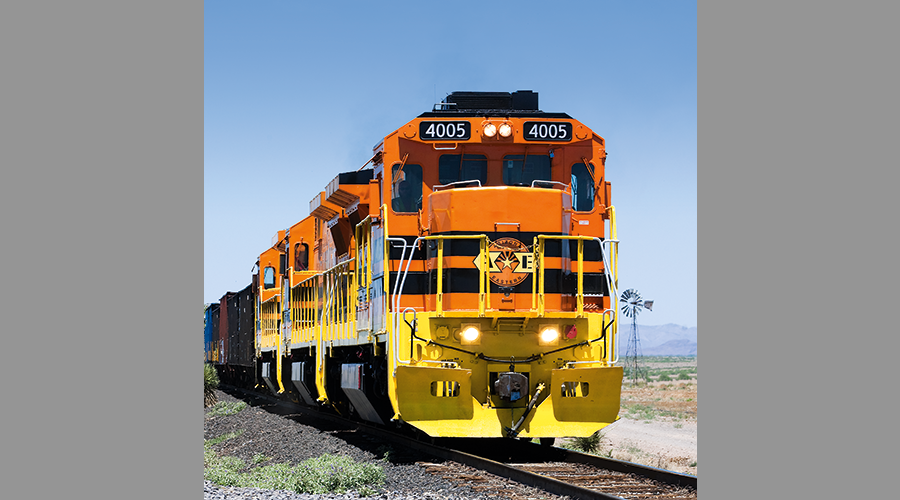

Rail News: Short Lines & Regionals

Profile: Dan Sabin, Iowa Northern Railway

Dan Sabin didn’t single-handedly prevent the Iowa Northern Railway Co. (IANR) from going belly-up in the 1990s. He had help from his family, employees, several Class Is, a number of shippers and others. But Sabin’s entrepreneurial spirit and recognition of a broken-down short line’s potential drove efforts that helped the railroad survive, then thrive.

Sabin, 59, is president of IANR, a 163-mile short line formed in 1984 following the liquidation of the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad Co. The railroad operates a mainline from Manly to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and a 20-mile branch line from Waterloo to Oelwein, Iowa. IANR interchanges directly with CN, Canadian Pacific, Union Pacific Railroad and the Cedar Rapids & Iowa City Railway, and indirectly with BNSF Railway Co., CSX Transportation, Kansas City Southern, Norfolk Southern Railway and Iowa Interstate Railroad Ltd.

When he assumed management of IANR in the mid-1990s, Sabin believed the long-struggling railroad could generate more traffic by promoting the short line’s multiple Class I connections, developing strong business relationships with shippers, improving infrastructure and bolstering service performance. He worked hard to nurture a number of relationships and obtain capital for much-needed trackwork, helping transform the railroad into the burgeoning short line he had envisioned. Now, more transformations are on tap: Within two years, annual operating revenue should reach the necessary Surface Transportation Board classification level — $21 million — for the short line to become a regional, and within four years, annual carloads should clip the six-figure mark.

“I know very few people that have the vision and the ability to see something that is very hard to be seen, and make that become a reality,” says Joshua Sabin, IANR’s director of administration, about his father. “It’s hard to get away from the words ‘passion’ and ‘energy’ and ‘true entrepreneur’ when describing him.”

Dan Sabin is a forward thinker who knows the rail industry well and his short line “doesn’t work like a big railroad,” says Harlyn Vanderlinden, manager of Dunkerton Cooperative, an IANR-served grain shipper in Dunkerton, Iowa. For 20 years, the co-op trucked all its grain to Cedar Rapids, but the short line recently helped Dunkerton design a larger rail footprint adjacent to new bins to load grain more efficiently. IANR also developed a two-tier rate structure after an ethanol plant opened eight miles away and posed a threat to the co-op’s market.

“Dan is always seeing things outside the box that the railroad can do for us and we can do for him,” Vanderlinden says. “He knows how to build relationships and make things work.”

IANR employees know that customers’ needs are paramount because they are trained early on to work with shippers and find ways to fulfill their needs, says Dan Sabin. Take care of customers and their business will grow, and in turn, so will IANR’s, he figures.

“I always tell people that if you have a dilemma, always err in favor of the customer, but don’t ever drop the ball,” says Sabin. “Do whatever it takes to serve the customer.”

A railroader’s railroader

Sabin has known what it takes to be a hardworking, customer-centric railroader since childhood. He was born into a railroading family in Manly. His father was an engineman for the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific from 1944 to 1976, and his four older brothers served the railroad as a clerk, signal maintainer, engineman and conductor.

Sabin joined the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific in August 1968 as a student train order operator at age 15, then became a train dispatcher at 18 — the nation’s youngest dispatcher at the time, he says — and a night chief dispatcher at 19. He worked nights while attending Grand View College and Southwestern Oklahoma State University, where he graduated in 1977 with degrees in economics and business administration.

Sabin joined CP in 1978 and spent the next four years in such posts as trainmaster, assistant superintendent and director of service planning system. In 1981, he joined the Chessie System as manager of operations planning and later served as superintendent of operations and superintendent of administration.

In 1987, Sabin co-founded Transportation Operations Inc., which provided consulting services to rail shippers, state governments and short lines. The business enabled him to develop short-line expertise, and hone his marketing and analytical skills.

Transportation Operations was involved in various-sized projects in North and South America, and eastern Europe. In 1988, the company began providing consulting services to IANR. While still involved with Transportation Operations in 1993, Sabin co-founded Iron Road Railways, where he was vice president, COO and CMO. The firm, which managed the start up of the Windsor & Hantsport Railway in Nova Scotia, Canada, provided Sabin short-line holding company experience.

He became part of IANR’s management team in 1994, when he left Iron Road Railways to focus on reviving the short line. Sabin, Iron Road Railways officials and former Chessie System-CSX Manager Pete Collins then jointly purchased IANR in November 1994, and Sabin became president. Sabin convinced his brother, Mark, who was an operating officer for the Chicago & North Western (C&NW), to join the short line a year later and head up operations.

IANR was in shambles when the partners purchased it, says Sabin. The short line originated just 235 revenue cars per mile, and handled about 1,000 loads and empties for C&NW between Waterloo and Manly-Cedar Rapids under a haulage agreement. The railroad owned five locomotives and 63 covered hoppers that made two trips per month to Cedar Rapids. IANR also employed 18 “over-worked and under-paid” workers, and only the most basic trackwork was performed, so train speeds couldn’t reach 25 mph, Sabin says.

“[IANR] was owned by grain operators along the line, and these were grain people, not railroad people,” he says. “The state held the mortgage on the railroad, and they were people who didn’t think the Rock Island would last, and so they wouldn’t allow them to spend money to do the job right.”

Sabin viewed IANR as a perfect situation to put his entrepreneurial skills to the test. He slowly began leasing more powerful locomotives, allocating motive power more strategically and purchasing more hopper cars. He also focused on much-needed manpower and track maintenance.

Keep track intact

Sabin learned early in his railroad career that well-maintained track is a top priority. So, he sought low-interest loans from the state of Iowa to obtain the necessary $5 million to $6 million for overdue trackwork. He then sold the rails on the line to Bank Boston and leased them back, receiving nearly $7 million to reimburse the state and replace ties.

Today, the short line employs 115, owns 25 locomotives and operates a leased fleet of about 450 hoppers. From 1994 to 2010, carloads more than tripled from 15,077 to 57,831; this year, Sabin projects traffic to increase 13.3 percent year over year to 65,524 units, and by 2015’s end, reach 100,000 units. He expects total revenue, which nearly quintupled from $4.2 million in 1994 to $20.7 million in 2010, to jump 32.7 percent to $27.5 million in 2011.

Operational and infrastructure improvements have enabled the short line to provide more reliable service, which has helped improve the railroad’s credibility with shippers, says Sabin.

“From ’95 to ’99, we did a tremendous amount of work. Then, we could go to the [Archer Daniels Midlands] of the world and work with them on moving their corn,” he says.

Corn traffic has played an integral role in the short line’s turnaround. There are large volumes of corn production on IANR’s line; in Cedar Rapids, major food processors grind about 1 million bushels per day. In 1994, the railroad originated about 1.1 million bushels of corn; this year, IANR expects to originate slightly less than 80 million bushels followed by a projected 91 million bushels in 2012.

Because the short line long has posed strong traffic- and revenue-growth potential, attaining it sometimes meant taking risks that other IANR owners weren’t comfortable taking in the early to mid-2000s — primarily spending money to continue bolstering infrastructure at a time when others would have held the line on expenditures, says Sabin. His solution: buy them out. Sabin assumed sole ownership of IANR in 2005.

A year later, he worked to obtain a $25.5 million Railroad Rehabilitation & Improvement Financing (RRIF) loan from the Federal Railroad Administration, and used the proceeds to buy back all the rails from the bank and continue bolstering infrastructure.

“I knew a lot of money had to be spent on the railroad, and once we purchased the line from others and could take some risks, that was huge,” says Sabin. By having [the RRIF loan] available to us, we could grow instead of survive.”

Nearly washed up

However, the railroad’s long-term survival came into question in the summer of 2008, when heavy rains flooded large parts of Iowa. Two major rail bridges were unusable and more than 25 miles of track were washed away. The customer relationships Sabin and his team had tried to carefully nurture paid off when several shippers prepaid for future service to provide IANR the necessary cash flow to remain in business.

“I think it was the long-term relationships that Dan had in place,” says Dunkerton Cooperative’s Vanderlinden, describing why customers came to IANR’s aide. “There’s a lot of trust and integrity with Dan. If he says something is going to be a certain way, he’ll do it.”

Several Class Is and the short line’s workers pitched in, too. UP provided a reasonably priced, long-distance detour so the short line could continue to move corn from its cut-off northern end to Cedar Rapids, and CN helped move equipment and traffic over its route between Cedar Rapids and Waterloo, says Sabin. Employees accepted pay cuts and worked four days a week after the floodwaters resided to retain cash flow and avoid layoffs.

Yet, the floods took their largest financial toll on the short line in 2009, when lost revenue and higher costs caused a cash crunch. A line of credit had been fully tapped and bankers wanted other stakeholders involved who would be willing to provide cash to the railroad, says Sabin.

To obtain an additional equity infusion, IANR reached a minority investment agreement last year with The Andersons Inc., which operates grain elevators, distributes fertilizer and leases rail cars. The Andersons obtained car repair capacity on IANR and the short line received proceeds that were used to replace a bridge in Black Hawk County that restricted weight loads for larger railroads, replace and repair rolling stock, and restructure and pay off debt.

The deal required that the short line be governed by a five-member board, including two directors from The Andersons, two from IANR and an independent director — a seat now held by Peter Rickershauser, a former BNSF vice president of short line development. Although Sabin still maintains a majority stake in the railroad, he admits it’s not the same as being the sole owner, especially managing “other people’s money.”

“But I expected it to be a lot tougher,” he says. “I enjoy working with all of [the board members].”

Sabin also continues to enjoy working with customers and connecting railroads to boost business. In 2007, the short line formed a logistics partnership with Manly Terminal L.L.C. and Hawkeye Energy Holdings that led to the creation of a 100-acre truck-to-rail ethanol originating terminal in Manly. The terminal also has developed into North America’s largest wind component distribution facility, primarily serving UP customers, according to IANR. Now, industrial development along IANR’s line is under way via a 165-acre Manly Logistics Park and a new terminal in Butler County.

Bond broker

Figuring out how to continue working well with customers and other railroads is key, says Sabin — especially since IANR is well past the trials and tribulations of the past few years. For example, he seeks to make the short line a leader in developing new bio-mass crop waste traffic via a recent Class I deal.

The short line reached an agreement with UP to operate its 28-mile Forest City-to-Belmond, Iowa, line via trackage rights over a CP segment between Nora Springs and Garner, Iowa. The line will provide IANR access to about 12 million tons of excess corn crop waste, helping to develop 2,500 carloads in 2012 and about 5,000 in 2013, Sabin estimates.

With two turnarounds notched on his belt, Sabin hopes the short line can stay the traffic- and revenue-growth path without more misfortunes. Yet, painful lessons learned from past journeys will help Sabin and his team set the railroad’s present and future courses. After all, there are other Class I deals to hammer out and other customer relationships to build on the way to obtaining regional status.

“I try to teach [employees] that every day is a major opportunity,” says Sabin. “We should look to see what we’ve done, what we’re doing and where we’re going.”

Desiree J. Hanford is a Chicago-based free-lance writer. Email questions to Progressive Railroading.

Keywords

Browse articles on Dan Sabin Iowa Northern Iowa Northern Railway short line short line railroadContact Progressive Railroading editorial staff.

2025 MOW Spending Report: Passenger-rail programs

2025 MOW Spending Report: Passenger-rail programs

Gardner steps down as Amtrak CEO

Gardner steps down as Amtrak CEO

Guest comment: Oliver Wyman’s David Hunt

Guest comment: Oliver Wyman’s David Hunt

Women of Influence in Rail eBook

Women of Influence in Rail eBook

railPrime

railPrime